African Student Social Entrepreneurs at UConn: The SUSI Program

January 2018, by Alexander Holmgren

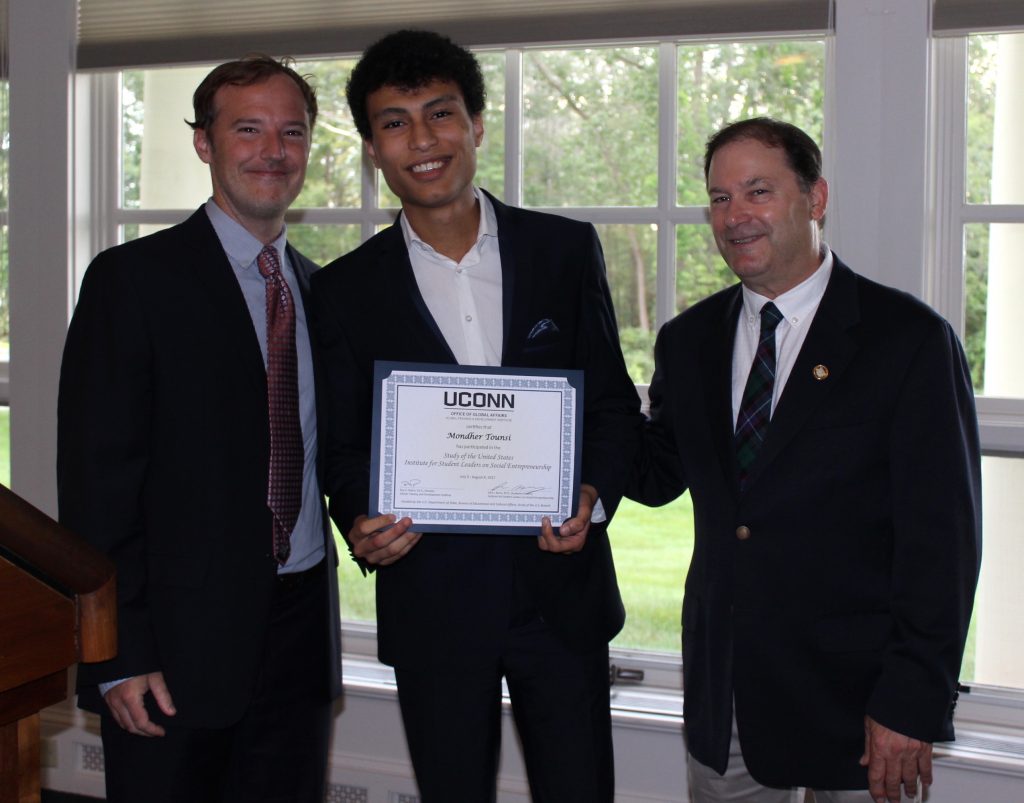

“Ce progr amme est un rêve (this program is a dream),” says Mondher Tounsi, a law student from Kasserine, Tunisia. He is referring to the Study of the U.S. Institute, or SUSI as it has come to be known, which is funded by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA).

amme est un rêve (this program is a dream),” says Mondher Tounsi, a law student from Kasserine, Tunisia. He is referring to the Study of the U.S. Institute, or SUSI as it has come to be known, which is funded by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA).

Every year since 2010, students have come to UConn from across Africa to participate in the SUSI program, which engenders mutual understanding and respect between foreigners and Americans through specialty exchange programs. The State Department’s ECA has awarded UConn’s Global Training and Development Institute (GTDI) over $3.5 million in contract awards to host the SUSI program over the past 7 years. The program’s academic director, Jack Barry, explains, “for the State Department, it is really an opportune chance to bring foreigners here and expose them to the United States with a broad focus in American history and culture, allowing them to engage in a reciprocal cross-cultural exchange with American citizens.” However, the SUSI program is distinct from many others of its type for its emphasis on Social Entrepreneurship. “The main idea is to help students launch start-ups or companies that have an effect or resolves a social problem,” explains Yousra Kherkhache, an Algerian student participating in the program, “gaining money and at the same time resolving a problem.”

At UConn, all SUSI program participants enter with an innovative idea on how to tackle a social problem in their community. Over the 5-week duration of the SUSI program, these students learn the skills necessary to launch their ideas as an organization or business. “They start off with a broad idea but no details worked out,” Barry explains. Through the SUSI program, he says, the students “build the plan for their social enterprise, which starts with a couple of paragraphs to, by the time they leave, a 4-5 page business plan with a lot of ideas fully sketched out.”

For Tounsi, The SUSI program provided the skills necessary to address serious problems in his community. Tounsi’s home-city of Kasserine has an unemployment rate 20% greater than Tunisia’s national average, the highest morality rate in the entire country, and a reputation for being an extremist hotbed. “It really makes me so sad to see this,” Tounsi says, especially because of the “lack of investment” in the people of Kasserine it prompts.

Tounsi has come up with an innovative solution: the Kasserine Catalyst, a youth hub where young people may gather to watch TV, play video games, or network ideas. His goal is to give the youth of Kasserine—who Tousni describes as “future entrepreneurs who want to launch their own initiatives”—a safe venue to develop and explore productive interests. Through the Kasserine Catalyst, he hopes to help these future entrepreneurs “dive into the world of entrepreneurship,” and, ultimately, “make a better reputation for Kasserine.”

The Kasserine Catalyst recently received a grant from the European Cultural Foundation and receives donations periodically from community members in Kasserine. Tounsi credits much of this success to his participation in the SUSI program and other Department of State initiatives. “It is now that we are really comfortable with the expertise we have to delve into very serious problems in Tunisia, such as extremism,” Tounsi says on his participation in the SUSI program. “Je veux vraiment remercier le programme qui m’a beaucoup aidé (I really want to thank this program that has helped me tremendously)” he says. “I am very excited to return to Tunisia. I feel a bit different and that I have a perspective that I want to share with everyone back home.”

Dalia Elgharib, an Egyptian student in business administration, likewise feels differently after her participation in the program that she describes as instrumental to the development of her project, Haya. “We have a severe problem with education in Egypt,” she says, “many Egyptian children are illiterate, and our schools are some of the lowest when scored for quality [of] education.” Elgharib attributes this problem to teachers, who in Egypt “are not trained how to interact with kids.”

Elgharib’s project strives to fill this skill gap through an incubation program for teachers that trains them on childhood developmental psychology, leadership, and interactive teaching methods over a 2-3 month period. She named her project Haya, which in Arabic means ‘let’s go,’ to inspire motivation—within herself as well as teachers. Elgharib identifies the largest obstacle to her project as persuading teachers to enroll in the program. Due to a low wage, Elgharib explains, most teachers host private classes to supplement their income, which makes them less likely to attend programs such as Haya. However, as a social entrepreneur, Elgharib recognizes the problem oftentimes encompasses the solution. Teachers compete with one another to attract students to these private tutoring sessions. Elgharib plans to incentivize teachers to enroll in Haya by marketing the program as an opportunity for teachers to draw more students to their private tutoring sessions.

Kherkhache, the Algerian student, took something different from the SUSI program than either Tousni or Elgharib: hope. “Not any country would do this,” she says, funding students to effect societal change in their communities. “I’m really grateful for this chance,” which will help her address a serious problem in her community: food contamination. Algeria lacks stringent food regulations, she explains, which result in high levels of food contamination for people in Algeria, particularly students. Kherkhache conducted a study and found that 235 people in the beginning of 2017 ingested contaminated food provided by their university. Unsure of what food may be contaminated, students are unsure of what is safe to eat.

But they won’t be for much longer. Kherkhache has developed an innovative solution to mitigate students’ ingestion of contaminated foods in the form of her for-profit SUSI project, Otlob Sihhi, which is Arabic for ‘Order Healthy.’ The project offers students a list of restaurants that are close, affordable, and, most importantly, regulated for food contamination. It also contract workers to deliver food from these restaurants via bicycle.

Fatima-Azzahra Benfares from Rabbat, Morocco, says the SUSI program for her is all about meeting other social entrepreneurs from North Africa. “The inspiration you get from the other people here, that is the most important for me,” she shares. According to her, only about a fourth of Moroccan women have jobs, oftentimes as fruit vendors in poor neighborhoods. These women, Benfares states, “are harassed for ten hours a day to get 6-10 dollars.” Not far from these women, students in richer areas would pay ten times that for fresh fruit, Benfares says. Taken together, she sees a unique opportunity to empower these women as entrepreneurs.

She started a franchise named Laymouna that contracts these women to sell their fruit to college students. Last year, Laymouna had its first test run as Benfares and a few entrepreneurs opened a fruit-stand on her university’s campus for a week; they sold-out everyday within four hours. “Believe it or not, people like fruit,” Benfares jokes. But despite its success, running Laymouna is not easy work. “What keeps me going is having an impact on these ladies,” who are able to nearly triple their income through participation in Laymouna, Benfares says. She shares the story of Raddiba, a fruit vendor who, like many others in Morocco, planned to marry a richer man for financial support. This changed soon after she joined Laymouna as an entrepreneur. “two months after working with us, she turned down his marriage proposal,” Benfares shares excitedly, “she feels empowered and wants to break that cycle.” Through the SUSI program Benfares hopes to expand Laymouna and empower more women like Raddiba.

Tousni, Elgharib, Kherkhache, and Benfares left the United States in August, but they continue to benefit from their participation in the SUSI program through the ECA’s International Exchange Alumni Program (https://alumni.state.gov/). This program permits them to apply for a three-year grant to further build the project they developed while at UConn. The impact is huge. GTDI Director Roy Pietro, who has served as the Principal Investigator for the SUSI program since its inception, elaborates, “the SUSI program supports the university’s academic vision of ‘promoting sustainable development and a happy, healthy, and inclusive society both locally and globally, based on intercultural understanding and recognition of the transnational nature of the challenges and opportunities we face.’ Meanwhile, the grant funding has allowed us to provide the SUSI entrepreneurs approximately $85,000 in mini-grants for over 150 social change projects in local communities throughout Africa.” The passion, efforts, and rewards of this year’s SUSI program alumni are sure to change the world, allowing UConn to expand its land grant mission beyond our national borders and young leaders from across Africa to help effect change in their communities.